Robert Irwin

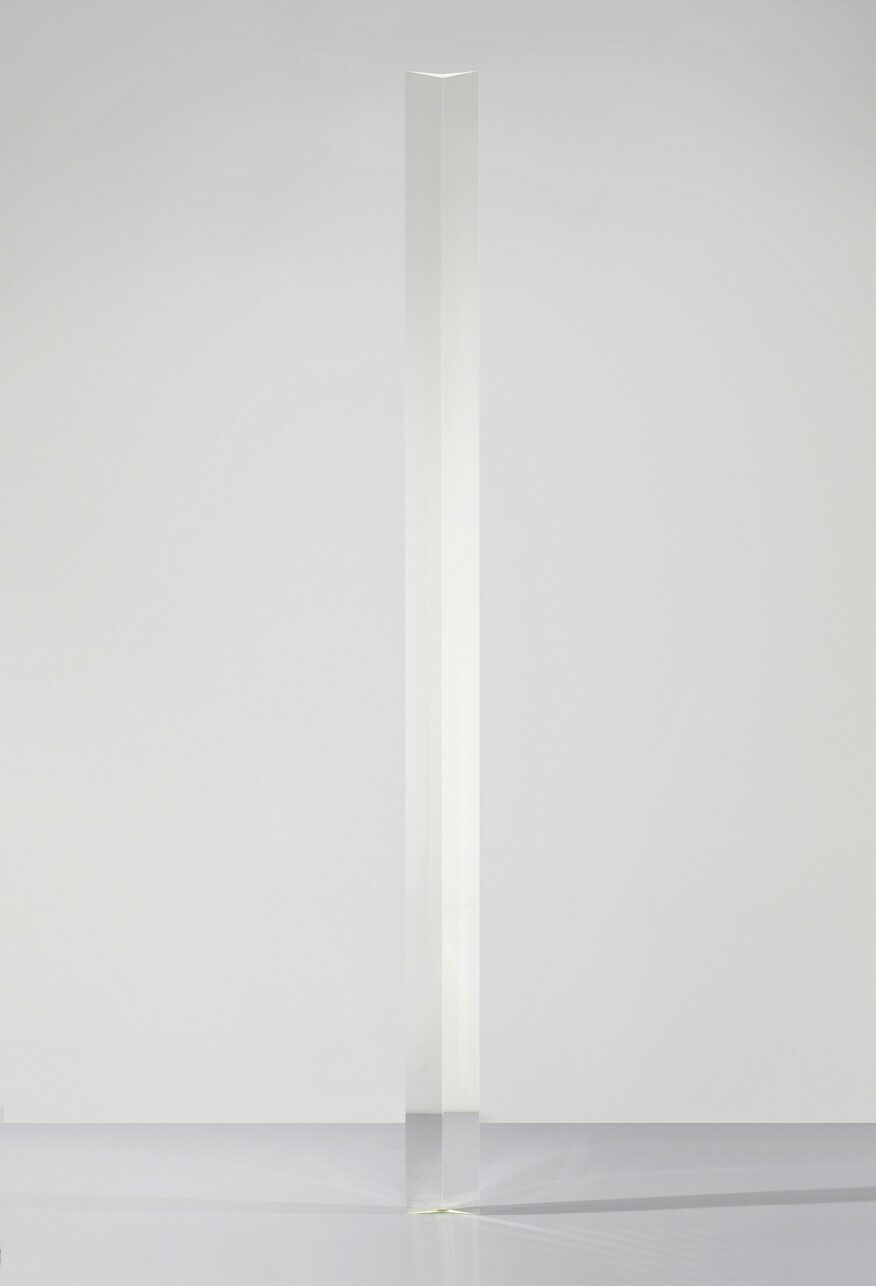

The collection opens with a column conceived by Robert Irwin in 1969.

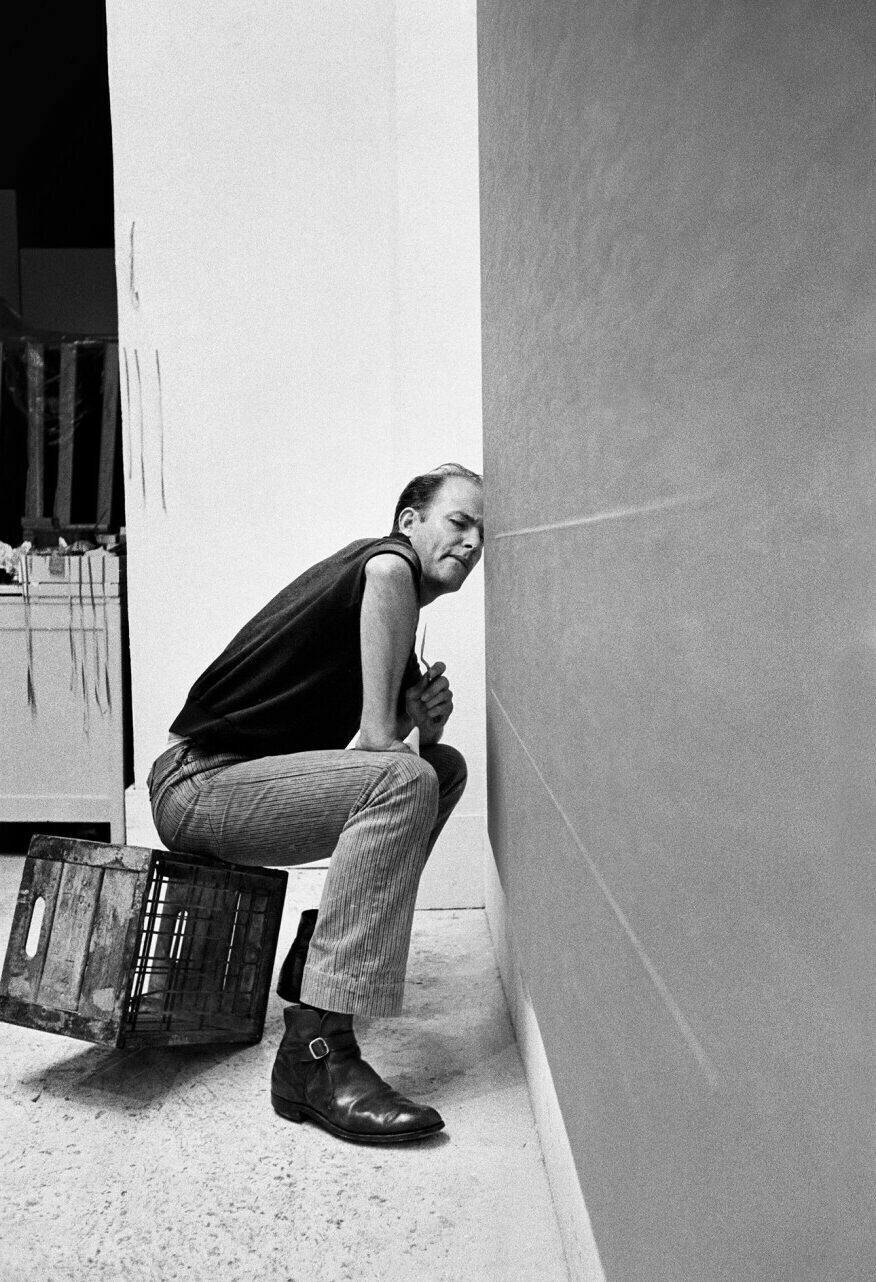

Originally trained as a painter, Irwin very early on moved away from the object-as-picture to focus instead on the conditions of perceptual experience.

Between 1965 and 1969, anticipating this column, he developed the Disc series. The object is still present, but already put under pressure: its contours dissolve, shifting the viewer’s attention towards the relationship between the work, the space that contains it, and—crucially—one’s own act of seeing.

In 1970, Irwin completely emptied his Californian studio, placing only this five-sided column of optical acrylic at its centre. Acting like a prism, the work is almost invisible, without any spectacular effect. It does not draw attention to itself. Rather, it subtly alters our experience of the place: it displaces it, destabilises it, awakens it. In doing so, Irwin makes perceptible our condition as sensing beings in relation to our environment. It is, if one wishes, the time of the body—prior even to that of words.

That same year, Irwin permanently closed his studio, abandoning the idea of making objects in favour of site-specific installations conceived for the lived world rather than the enclosed space of the studio. He described his art as “conditional”, meaning that the work never exists as an autonomous object, but always within a given situation.

Within the Brussels collection, because the house that hosts the work does not belong to us, we had to place the column on a platform. This solution is not ideal: it assigns the work the status of a sculptural object to be looked at, whereas Irwin’s entire practice seeks to move away from the object in order to foreground perception as the medium itself. We nevertheless chose to live with it here, while promising ourselves that one day it will find a more appropriate setting. Personally, I imagine it particularly at ease in the corner of a Venetian portego.

Finally, it should be noted that Irwin—like many artists associated with the Light & Space movement—did not wish his works to be photographed. They are not fixed images carrying a content to be received, but devices that actively engage perception, and as such can only exist through experience.

What is offered here, therefore, is not so much an image of the work as an invitation to come and experience it.

La collection s’ouvre sur une colonne conçue par Robert Irwin en 1969.

Formé à la peinture, Irwin se détourne très tôt de l’objet-tableau pour s’intéresser aux conditions de l’expérience perceptive.

Entre 1965 et 1969, annonçant cette colonne, il réalise la série des Disques, dans laquelle l’objet est encore présent, mais déjà mis en crise : ses contours se dissolvent, déplaçant l’attention du spectateur vers la relation entre l’œuvre, l’espace qui l’abrite et… son propre regard.

En 1970, Irwin vide entièrement son atelier californien pour n’y placer que cette colonne en acrylique optique à cinq faces, qui agit comme un prisme. Sans effet spectaculaire, presque invisible, l’œuvre n’attire pas l’attention sur elle-même. Elle modifie subrepticement notre expérience du lieu : elle la décale, la rend instable, la réveille. Ce faisant, Irwin rend perceptible notre condition d’être sensible à son environnement. C’est, si l’on veut, le temps du corps — avant même celui des mots.

Cette même année, Irwin ferme définitivement son atelier, abandonnant l’idée de fabriquer des objets au profit d’installations site-specific pensées pour le monde vécu plutôt que pour l’espace clos de l’atelier. Il décrit d’ailleurs son art comme “conditionnel”, signifiant par là que l’œuvre n’existe jamais comme un objet autonome, mais toujours au sein d’une situation donnée.

Au sein de la collection à Bruxelles, la maison qui l’abrite ne nous appartenant pas, nous avons été contraintes de placer la colonne sur une plateforme. Ce dispositif n’est pas idéal : il lui confère un statut d’objet sculptural à regarder, alors même que tout le travail d’Irwin tend à se défaire de l’objet pour mettre en lumière la perception, devenue le médium. Nous avons néanmoins choisi de vivre avec elle ici, en nous promettant de lui offrir, un jour, un emplacement plus propice. Selon moi, elle serait particulièrement heureuse dans le coin d’un portego vénitien..

Il faut enfin préciser qu’Irwin — comme nombre d’artistes associés au mouvement Light & Space — ne souhaitait pas que ses œuvres soient photographiées. N’étant pas des images fixes porteuses d’un contenu à recevoir, mais des dispositifs engageant activement la perception, elles ne peuvent en effet exister que dans l’expérience.

Ce qui est donné ici n’est donc pas tant une image de l’œuvre qu’une invitation à venir l’éprouver.